Floods are among the most destructive and recurring natural disasters worldwide. In 2025, the scale and frequency of damaging flood events—flash floods, riverine floods, coastal storm surges, and urban pluvial flooding—are drawing renewed attention from scientists, policy makers, insurers, and communities. This article, Climate Change and Floods: Why Disasters Are Increasing in 2025, explains the science and drivers behind the trend, the tradeoffs society faces when choosing responses, the limits and challenges of different approaches, and the broader impacts on daily life, industry, and governance.

Why floods are increasing: the physical drivers

1. A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture

Warmer air can hold more water vapor, so when conditions trigger heavy rainfall, storms are capable of producing much more intense downpours than in the past. Observational records and climate assessments show an increase in the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events across large land regions, which directly raises the risk of rainfall-driven and flash flooding.

2. Changing storm dynamics and extremes

Climate change is altering storm tracks, monsoon behavior, and the intensity of tropical cyclones in some basins. These changes can concentrate more rainfall over specific regions or prolong rainfall episodes, increasing river flows and overflow risk. Remote-sensing and modeling studies in recent years indicate heavier, longer, or more frequent rain episodes in many vulnerable regions.

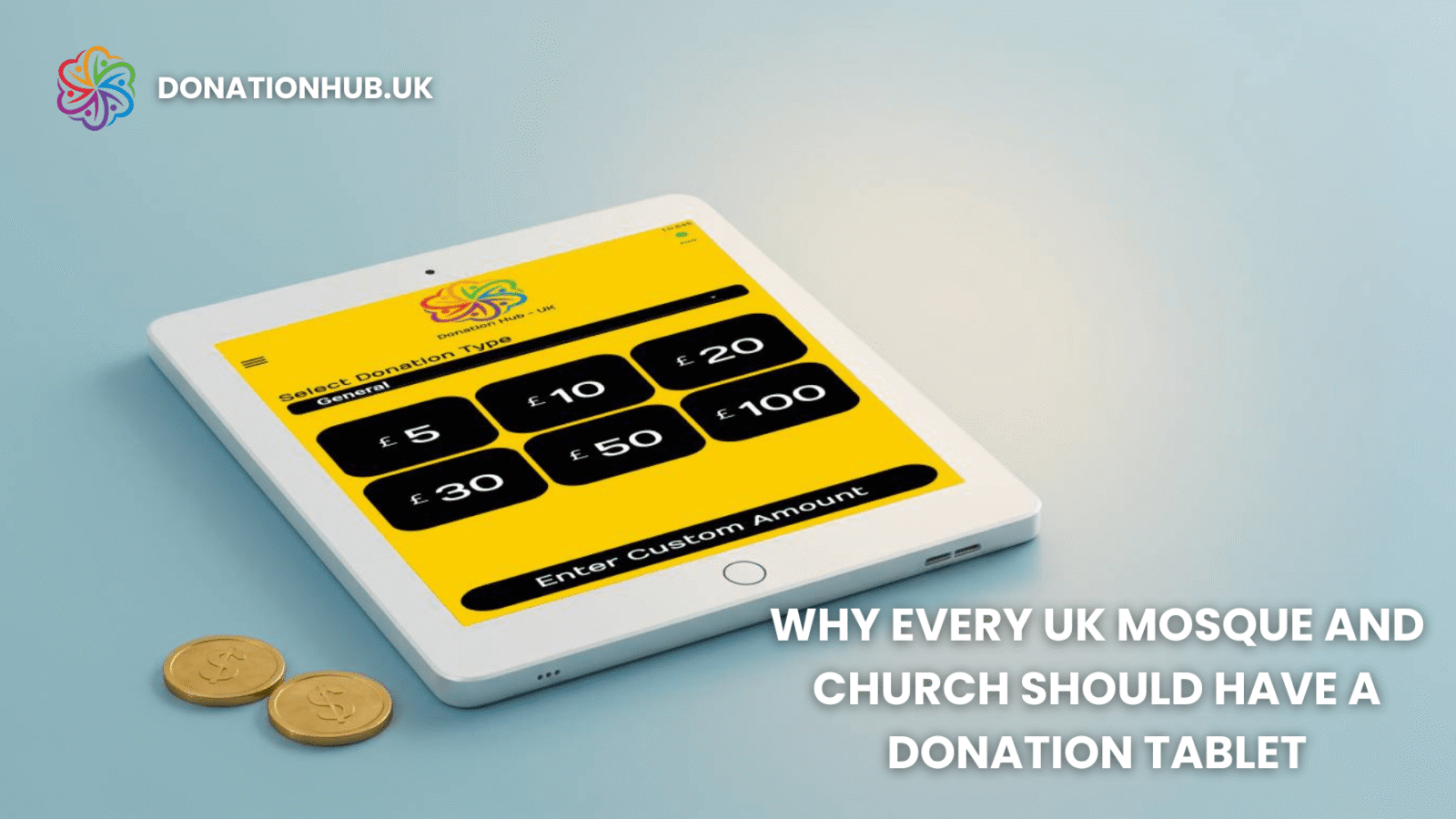

Just as communities prepare for floods with the right tools, mosques and charities today are also adopting smart solutions like the Donation Tablet to make giving faster, easier, and more transparent.

3. Sea level rise and coastal flooding

Rising sea levels magnify the impacts of storm surges and high tides; what used to be a relatively rare coastal flood can become a yearly or seasonal nuisance. This coupling of higher baseline seas plus more powerful storms increases coastal inundation risk and the geographic area exposed to flooding. (See also national and regional risk reports that flag more coastal properties becoming uninsurable under unchecked warming scenarios.)

4. Land use change and urbanization

More people living in cities, often in low-lying or poorly drained areas, combined with impermeable surfaces (roads, concrete), reduces natural absorption of rainfall and increases urban runoff—leading to more frequent pluvial floods. Research shows urban flood exposure has grown substantially in the Global South and continues to rise with unplanned development.

Human and socioeconomic drivers that amplify flood impacts

- Population growth in flood-prone zones. As urban population increases and housing expands into hazard-prone floodplains, the number of people and assets exposed rises—even if the hazard itself were stable. UN risk assessments find steadily rising exposure numbers.

- Aging or inadequate infrastructure. Drainage systems, dams, levees, and reservoirs built for past hydrological regimes may be insufficient under new extremes. Maintenance backlogs and underinvestment increase vulnerability.

- Socioeconomic inequality. Low-income communities often occupy the riskiest locations and have the fewest resources to prepare, evacuate, or rebuild—making flood impacts disproportionately severe for marginalized populations.

Tradeoffs: mitigation vs adaptation (and why both matter)

Mitigation (cutting greenhouse gas emissions)

Pros: Slows warming and reduces the long-term rise in flood risk globally; benefits are systemic and long-lasting.

Cons: Mitigation operates on multi-decadal timescales; reductions now will not prevent many near-term changes already “locked in” by past emissions.

Donation Tablets make it simple for mosques and charities to collect support instantly.

Adaptation (reducing vulnerability now)

Pros: Immediate protection—flood defenses, early warning systems, land-use planning, and resilient infrastructure can save lives and reduce costs today.

Cons: Adaptation can be expensive, sometimes produces perverse incentives (e.g., encouraging development behind levees), and may require repeated investments as extremes intensify. Choices must balance short-term protection with long-term sustainability.

The pragmatic choice is both: aggressive mitigation reduces long-term hazard growth, while adaptation reduces current exposure and helps communities cope with floods today. Financing and governance determine how well societies balance these priorities.

Challenges of different approaches

Hard infrastructure (levees, sea walls, dams)

- Advantages: Can protect large urban or economic centers and are politically visible.

- Challenges: High upfront cost, possible ecological damage, maintenance needs, and potential for catastrophic failure. Hard infrastructure can also encourage development in exposed zones (moral hazard).

Nature-based solutions (wetland restoration, floodplain reconnection)

- Advantages: Provide co-benefits—biodiversity, carbon sequestration, water quality—and can absorb flood energy naturally.

- Challenges: Require space, may conflict with land-use needs, and often provide lower levels of protection compared with engineered defenses for extreme events.

Early warning & community preparedness

- Advantages: Cost-effective, saves lives, and empowers local response.

- Challenges: Dependent on communication infrastructure, public trust, and timely evacuation routes; may be less effective in sudden flash floods.

Financial instruments (insurance, risk transfer)

- Advantages: Distribute risk costs and aid recovery.

- Challenges: Rising risk can make premiums unaffordable or insurers withdraw coverage, shifting burden to governments and households—especially problematic in regions where many properties become uninsurable. Recent national reports highlight this growing insurability challenge.

Broader impacts on society, industry, and daily life

Public health and displacement

Floods cause immediate injuries and deaths, but they also bring long-term health burdens: waterborne disease, mental health impacts, and mold-related respiratory conditions. Displacement and repeated losses erode livelihoods and social cohesion.

With a Donation Tablet, giving becomes cashless, quick, and transparent.

Economic costs and supply chains

Floods damage housing, infrastructure, agriculture, and industry—creating cascading economic effects. Global assessments show disaster costs rising, with floods responsible for a large share of people affected and significant economic losses. Disruptions to transportation and manufacturing also ripple through global supply chains.

Insurance markets and finance

Insurance premiums are rising in flood-prone areas; in some cases, insurers may withdraw, leaving homeowners exposed. This has consequences for mortgage markets, investment, and public budgets when governments step in after major events.

Urban planning, housing, and migration

Long-term exposure can force difficult policy decisions: restrict development in hazard zones, buy out repeatedly flooded properties, or invest heavily in protection. All options involve tradeoffs—economic, social, and ethical—and often meet resistance from affected communities. Potential migration from persistently high-risk areas raises additional social and political challenges.

What effective responses look like in 2025

- Integrated risk management: Combine nature-based measures, engineered defenses, early warning, and land-use policies so that no single approach must bear the entire burden.

- Targeted finance: Channel funds to vulnerable communities for resilient housing, drainage upgrades, and rapid response capacity. International aid and risk-sharing mechanisms remain crucial for developing countries.

- Data and forecasting: Invest in observation networks, satellite monitoring, and flood mapping to improve forecasting and planning. Advances in satellite radar and AI-based flood mapping are revealing previously hidden exposures and helping prioritize interventions.

- Policy and insurance innovation: Develop affordable, adaptive insurance and public-private risk pools that incentivize resilience rather than simply subsidizing repeated rebuilding.

- Community engagement: Preparedness plans work best when communities are involved in design and implementation—local knowledge improves evacuation routes, shelter location, and social support systems.

Conclusion

Climate Change and Floods: Why Disasters Are Increasing in 2025 is not a single-cause story—it’s the result of interacting physical changes (warmer air, altered storms, sea level rise), human drivers (urbanization, land-use change), and socioeconomic choices (where and how we build, who pays for protection). Scientific evidence and recent global assessments underscore that heavy precipitation and flood exposure are increasing in many regions, and that the costs of inaction are already rising.

The practical response is two-pronged: accelerate mitigation to limit future increases in hazard, and scale up adaptation—especially for the most vulnerable—to reduce harm now. Policymakers, communities, and industry must weigh tradeoffs: immediate protection versus long-term sustainability, engineered infrastructure versus nature-based solutions, and private insurance versus public support. In 2025, those choices will shape whether communities become more resilient to floods—or more deeply exposed to the next disaster.